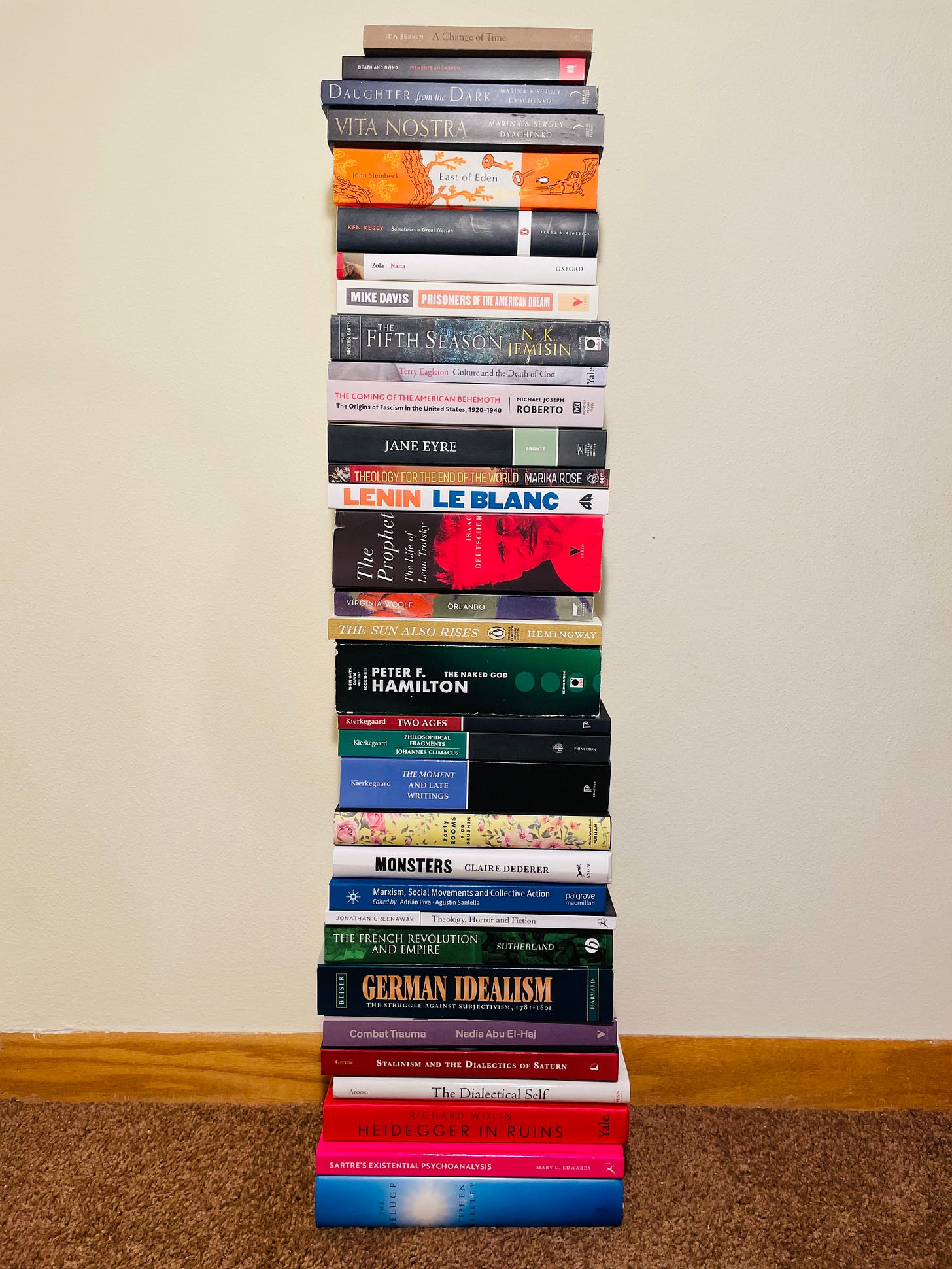

Since starting this Substack, I’ve only managed to post one new thing (everything else I have posted here is from my old blog). Part of this is because I can often be a bit neurotic, overthinking little things, or because my thought tends to ‘sprawl’ a bit, so any attempt to get from A to B eventually starts to develop a dozen little detours, which makes it hard to finish anything. In the interest of trying to teach myself to maintain focus, I thought I’d try something new and write some retrospective thoughts on the last year of reading. This is less a series of reviews of everything I read and more some thoughts on books that stood out to me. Any books not covered might’ve been perfectly good, I just have no thoughts to put down about them. Now I need to hammer this out before nursing school starts, because I’m not naive about how much time I’ll have to write once the semester starts next week…

Nonfiction

Wolin, Richard. Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology (Yale, 2023).

I can’t quite remember, but I think this was the first book I finished this year, and what a way to start off. If you’ve read The Politics of Being much of this will be a sort of repetition, as Wolin’s main thesis hasn’t changed all that much in the last couple decades. Essentially, Heidegger’s philosophical work is inseparable from his participation with the Nazi party, although admittedly it can be difficult to see for readers not intimately familiar with the context. It feels weird to say I had an emotional connection to such an academic text, but Heidegger really was a major influence on me when I was younger, and even now I can still feel myself ‘responding’ to him in how I think now.1 This isn’t to say the text isn’t academically rigorous, just that I had a very personal response to it, although I have little to add at the moment that I haven’t already said elsewhere. Similar to Losurdo’s big book on Nietzsche, Wolin teases out the hidden political implications of Heidegger’s more esoteric form of thinking by showing it was addressing a concrete situation, and what appears to be wistful meditation is really a cultural and political intervention, one comfortably at home with the reactionary movements he tethered himself to. The recent publication of many of Heidegger’s private notebooks gives him a lot of extra material to work through and wrestle with, but it really only fills in gaps in his published output without substantially changing it’s direction. Perhaps most damning of all, however, is the first chapter which points out the quantity and intensity of complicity there has been among several generations of Heidegger scholars to smooth over his rougher political statements. Editors, translators and the managers of Heidegger’s literary estate have ensured that we have not had full or proper access to everything, and that our access has been through a distorting lens that makes it difficult even today to know the extent of Heidegger’s reactionary politics. Wolin’s book is excellent, but sadly not the last word on the topic.

El-Haj, Nadia Abu. Combat Trauma: Imaginaries of War and Citizenship in Post-9/11 America (Verso, 2022).

I had the pleasure of interviewing Nadia about this book, and I’m glad to have done so because she’s not only an incredibly pleasant person to talk with but also an incredibly important scholar. This book deserves more readers to unpack and develop the history she uncovers here. The basic argument is that PTSD as we understand it emerged largely in response to American soldiers in Vietnam and their complicity in disturbing and violent acts. Part of the healing process was political reckoning and critique; the men might’ve mostly been draftees, but they still had to understand their part in a larger imperial machine. The healing process and political critique and activism were intertwined. Fast forward several decades and this understanding of PTSD has been replaced by a narrative of victimhood on the part of soldiers who’ve encountered something incomprehensible. This incomprehensibility means that those of us who’ve not served can’t really critique their actions. There’s an implicit epistemology here, one where veterans are in their own little world unavailable to civilian understanding, and so civilians can’t really participate in political critique of combat or its contexts; we can only thank veterans and try our best to help them reintegrate into our world. This leaves us stranded in a world where war and destruction are naturalized, soldiers are always heroes and civilians have no place in critical discussions of war. I’m not doing the narrative or all of El-Haj’s scholarly rigor justice, but the book clicked with me because it managed to give a concrete historical genealogy to something I’ve often felt but haven’t quite known how to discuss, so for that I’m deeply thankful.

Davis, Mike. Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the Working Class (Verso 2018).

Writing a book about contemporary politics has always seemed like an exercise in futility to me, since the chances of it still being relevant by time of publication, nevermind a few years down the road, is fairly slim considering how fast things change, and trying to keep up with all the new titles in the ‘Current Events’ section of your local bookstore (each title covered in blurbs claiming you must read this) has always felt equally futile. With that said, Mike Davis’ Prisoners of the American Dream has hardly aged a day since it’s original 1986 publication. The first is a long look at the structure of the American working class as a way of asking why there has yet to be a mass workers party in the United States in the same way that most European nations have. As with Davis’ biggest influence, Karl Marx, the simplistic dichotomy of proletariat and bourgeois doesn’t really capture the complexity of the analysis on hand, nor is it ever a simple tale of good workers and evil bosses. Instead, various competing and overlapping structures create contradictory forms of life, politics and struggle, and the structures that have defined America have made it difficult for a mass workers party to emerge, leaving us stuck with two parties, neither of which are friendly to workers interests. This leads into the second half of the book, a reflection on the last several years (at time of writing, the late 70’s and early 80’s). He charts the rise of the new right and it’s culmination in Reaganism, as well as the response by the Democratic party, which was to lean into many of Reagan’s ideas, shutting out the more progressive alternative in the form of Jesse Jackson’s rainbow coalition. When that plan didn’t work out for them, the Democratic establishment lashed out at Jackson and his colored voting base, decrying them as immature and entitled, essentially telling them to take a hike. The book ends with some reflections on changing economic and political dynamics, and the possibility of a revolutionary left alternative emerging in the United States, a question with an even greater urgency today than when Davis wrote.

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trostsky (Verso, 2015).

A couple years ago when I interviewed Bryan Palmer for the first time about James Cannon,2 he said he considered the best Marxist biography to be Isaac Deutscher’s massive trilogy on Leon Trotsky, saying that what sets it apart so well is it’s capacity to contextualize Trotsky’s life in the turbulent politics he participated in, as well as the social and economic context those politics tried to intervene in. While not a terribly friendly introduction for beginners,3 anyone looking for a detailed survey of Trotsky’s life and times will struggle to find anything better, especially from a more sympathetic perspective. Deutscher’s decade of research paid off; the portrait that emerges is detailed and compelling, although not uncritical. Trotsky had a bold personality that occasionally looked before he leapt, and he did fail at critical political moments to do what was necessary to carry on the revolution. However, these don’t detract from the overarching narrative his life gives us, or the image of what a lifelong commitment to the revolutionary project may look like. One also feels the profound emotional arcs; the exile in his early years that were eventually turned around and turned into revolutionary victory, only to then be slowly turned around again, resulting in further exile and eventually assassination, his life feeling like a microcosm of the world around him as it slowly but surely moved towards war. Perhaps it’s heresy to try and read a life so poetically, but it’s hard not to. As a final word, if you do decide to give this a go, consider finding each volume individually instead of reading the single-volume edition like I did; your hands will thank you for not making them hold open a 1600-page book for hours.

Kierkegaard, Soren. The Moment and Late Writings (Princeton, 1998).

Where much of Kierkegaard’s work can often feel aloof and indirect, the late attack on Christendom is a moment where the mask comes off, the metaphors disappear and a direct assault is launched against the priests and pastors of his day. This might seem like an obscure theological debate, but considering how intertwined the Church was with the state at this time, there’s a profound political attack that’s undeniably a part of this. Kierkegaard’s witty tongue remains active as he breaks the rule that we should not speak ill of the dead, attacking a deceased pastor and anyone who might defend him as a ‘truth witness,’ trying to resuscitate a more radical form of Christianity that’s been buried over. While it’s hard to know exactly how to place it in Kierkegaard’s bizarre and mazelike authorship, it’s a highlight for me and feels more like a culmination than anything as he takes aim at the very institutions that are getting in the way of us becoming ourselves. Further confirmation of this suspicion was also provided in Jamie Aroosi’s The Dialectical Self, which further confirmed the radical politics I’d always felt in Kierkegaard, but hadn’t quite known what to do with.

Dederer, Claire. Monsters: A Fans Dilemma (Knopf, 2023).

Claire is a very anxious woman, and because of that she struggles to come up with an answer to the question she raises: what do we do with art that we love when it’s produced by problematic people? However, I do think it’s a worthwhile question, and even if Dederer can’t quite answer it, watching her wrestle with it felt like watching a larger cultural problem play out. She sets the book up as a sort of memoir of being a fan; a fan of certain filmmakers, musicians, artists and tries to sort out her own feelings. This is valuable stuff to take into consideration, but she occasionally loses the plot a bit as she goes from investigating artists who were genuinely abusive to wondering if she is also an abuser of sorts, since she has taken time away from her kids to write. This is bizarre and wrong, but also in my opinion a quite telling moment, since it betrays a sort of neurotic paranoia about being a good person, which I think unconsciously informs her quest to figure out how to enjoy problematic art. Again, I think this is a worthwhile question, and Dederer’s quest, even if it doesn’t get us an answer, does tell us something about the modern paranoia surrounding our need to be good people.

Nonfiction

Grushin, Olga. Forty Rooms (Putnam, 2016).

This was the last novel of Olga Grushin’s I had yet to read, and it stands out from her other work in just how hard the ending smashes you in the gut. In her own way she is reminiscent to me of the existentialist insistence on our freedom and our need to face our lives honestly and authentically, against the various temptations to be carried along by the inertia that usually makes our decisions for us. This book is no different, and traces the lifetime of a young girl, initially interested in the more bohemian life of a poet, only to eventually find herself a heavily domesticated housewife with several children. Alienated from everyone around her, most of all herself, she spends her life wandering rooms filled with dresses bought online while working through a nonstop flow of wine, occasionally confronted by memories of the version of her that used to be, that could’ve been. Grushin doesn’t pull any punches with this book, and for that it has remained stuck in my head since reading it, refusing to leave me alone.

Markley, Stephen. The Deluge (Simon & Schuster, 2022).

I picked this up because someone on Twitter described it as ‘The Ministry for the Future but good’ which felt like a blurb directed at me personally,4 and it’s also how I’d describe it, having charged through all 900 of its pages in just a few short weeks. What really drives it is not it’s lengthy explorations of the science of climate change or the political mechanisms that need to be navigated to develop any sort of response, but the fact that the book is, at it’s core, a character study. You’ll follow a cast of half a dozen main characters, all with heavily distinct personalities, and you see them all internalize and cultivate responses to climate change that are undeniable reflections and expressions of them as individual human beings. In this way the book shows how we are often dealing with the most intimate and human aspects of ourselves when participating in history, how that epic sweep often reveals the things about us closer to us than we ourselves are, to paraphrase Augustine. The combination of a massive historical epic and precise psychological insight is reminiscent of the best of writers like Steinbeck, and speaking of…

Steinbeck, John. East of Eden (Penguin).

I’d only read Of Mice and Men before this, and that was back in high school when I was admittedly not a huge reader, so I went in with little notion of what I was in for aside from the fact that the novel is considered to be one of the great American novels. As with The Deluge I was swept away by the historical scope of Steinbeck’s vision that carried along the human beings dragged along with it over the course of decades. While the book didn’t always keep pace, the slower moments often include philosophical ruminations that contextualize the characters and their lives, filled with guilt, angst and desire. Admittedly not all classics pull me in and I read them more to try and push myself to read more challenging material, but I had little trouble connecting to East of Eden, and hope to reread it at a later date.

Marina and Sergey Dyachenko. Vita Nostra and Daughter from the Dark (Harper Voyager).

I’m including these together because while I think Vita Nostra was the stronger of the two, both these novels caught me completely off guard, dragging me into worlds that felt familiar and yet oddly alien. I wish I had something more interesting to say about them beyond saying they’re brilliant and you should absolutely pick them up and I hope that I have more to say upon finishing The Assassin of Reality this year (the sequel to Vita Nostra, and the middle entry in a trilogy). Making something surreal and twisted out of everyday life is a challenge; you need to understand the logic of two worlds, that of your reader and that of your characters, and then you need to build bridges between the two so that by time the reader realizes they’re somewhere new, it doesn’t feel too jarring. Within relatively short spaces, the Dyachenko’s manage to do that, pulling you into their bizarre alternate realities in such a way that it still feels natural, and your suspicions are just as likely to be directed at your own world. It’s a magic trick of the best sort, the one that would still seem miraculous even if they showed you how they pulled it off.

I wrote in more detail about this earlier in the year.

Contexts of Writing, Contexts of Reading

The first time I had any Heidegger assigned in a class, we read an essay out of his Pathmarks collection, “Phenomenology and Theology”. It was Fall of 2014, so the lecture came with the caveat that Heidegger was a Nazi, and there was some ongoing controversy over the recent publication of his private notebooks, although the professor felt things were be…

https://newbooksnetwork.com/james-p-cannon-and-the-origins-of-the-american-revolutionary-left-1890-1928

For that, Paul Le Blanc’s much shorter biography should suffice as an introduction to Trotsky’s life from a sympathetic perspective.

Tales of Revolution

It’s hard to know in this day and age what novel’s are supposed to be doing. I’m not even always sure what I’m looking for, even given my own politics. It’s easy to assume that someone involved in a revolutionary Marxist international would simply want depictions of revolution or the working class, although I also suspect Marx or even Trotsky would’ve s…