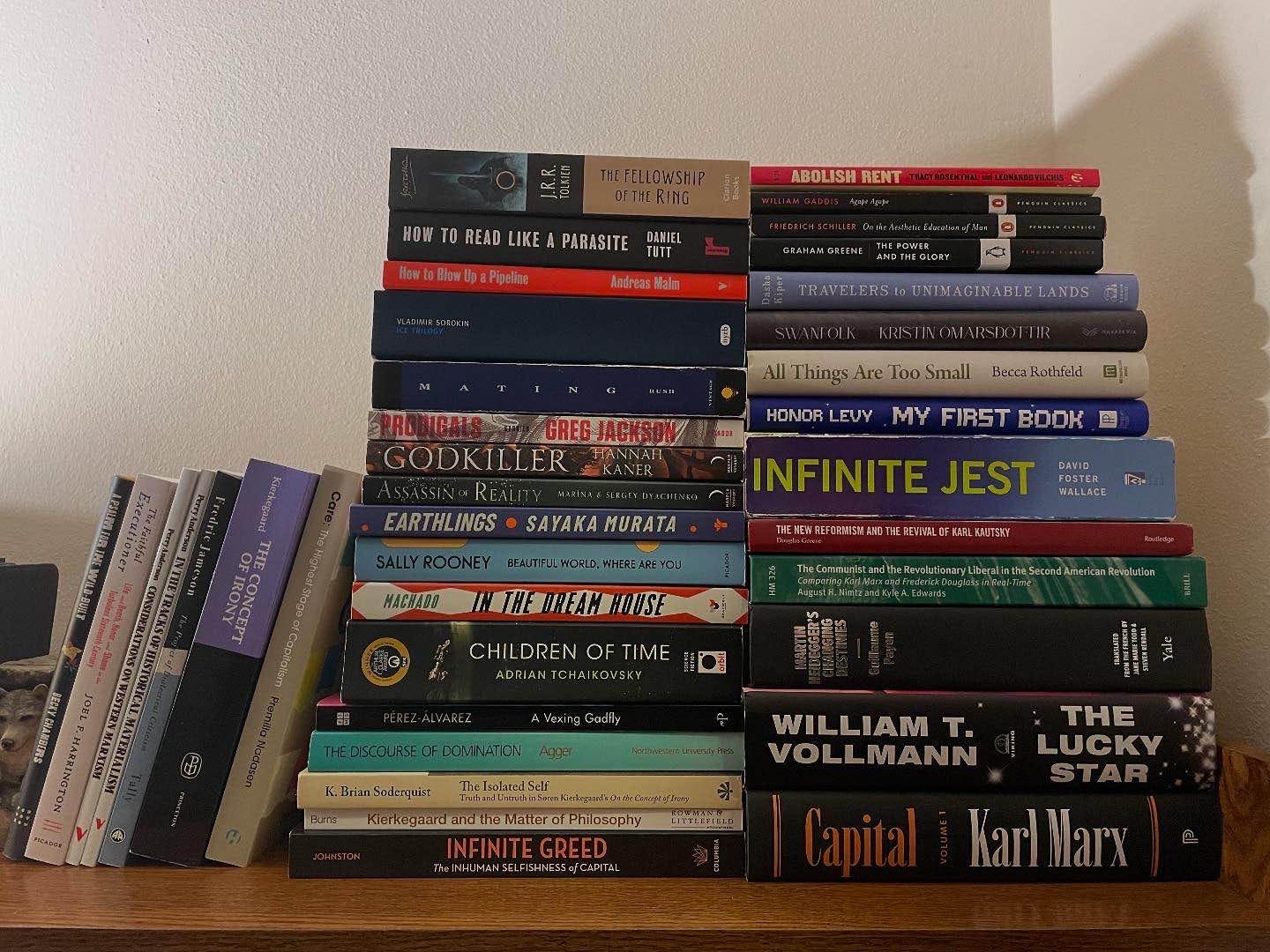

As with last year, these are not really reviews so much as reflections on the things I read. Things I think and feel about books I managed to get through. I’m doing myself a favor and sparing myself the need to do hardcore analysis of the texts in question, instead just trying to articulate my own thoughts. Some of these might become their own essays at some point if I ever find the time because I have more to say, and there were plenty of other books I read that I’m not bothering to cover here. I read a biography of Heidegger1 that didn’t really add much to my picture of him, several books on Kierkegaard2 that might appear in an essay on Kierkegaard at some point, but didn’t really feel like they needed to be addressed on their own. I read some fantasy3 and sci-fi4 that were the openers to bigger series, and I mostly read them as entertaining asides and breaks from memorizing pharmaceutical side-effects than anything. I’m still not sure what I’m doing with all these, not sure why I’m still writing about what I’m reading or even why I’m reading what I’m reading at this point. Sometimes a publisher sends me a book in the hopes that I can do a podcast about it, which is fine, but as for the rest of it I’m admittedly not always sure. I guess some part of me still thinks there’s something to be learned from books, and that part of the learning process involves trying to respond and articulate my thoughts about them as much as my schedule currently allows. Someday when I’m older I’ll maybe write a multi-volume study called What I’ve Believed and map out in detail the journey I’ve taken through my personal library. It will consist of only a few sentences in the main text, everything else in the footnotes (which you may have noticed I’m somewhat neurotic about) and the bibliography. Until then, we’ll have to settle for this.

Fiction

William Gaddis, Agapē Agape (2002)

I’ll admit this one frustrated me, but not because of its difficulty. Like all of Gaddis’ work, it is not an easy read, a nonstop rambling from someone in their final days, succumbing to disease, caught between pain and painkillers, as well as the ambitions to write a final masterwork on the history of the player-piano and the increasingly limited time permitted to them to finish it. This all parallels Gaddis’ own final days as he succumbed to prostate cancer. The book is a ceaseless raging against the dying of the light, and in a way it is beautiful, in its own furious, spiteful sort of way. I’ve dealt with a lot of death in my own life as a caregiver, and not enough literature seems to take it seriously, which is unfortunate considering how powerful the end can really be. And yet I found Gaddis particularly frustrating in how he faced it because most of his rage is directed against the common man, the lumpen, the proles, the volk and the anonymous anyone. They’re a simple, stupid lot who have little appreciation for great art, whether it’s a 900-page Gaddis novel or his fictional history of the piano-player. They want simple, conclusive answers in easy prose and a clear plot, all wrapped up in a reasonable amount of time. They’ve lost their ability to read anything challenging, to work and wrestle with ambiguity, or stick with something for more than the length of an average TikTok. This rubbed me the wrong way because I read this just as I was starting nursing school this year, and would read this book a few pages at a time in between memorizing pharmaceutical side-effects, getting points taken off for putting my gloves on incorrectly and getting up at 4:45am to be on the floor for a 6am clinical. To then come from all that and read a steady beratement of myself and my classmates for not reading enough challenging literature and preferring the easy comforts of sitcoms and sports on television was a bit of a trip, especially as the narrator (and I assume Gaddis himself) spent his final days under the care of a personal nurse. I don’t remember any inquiries about what she does in her spare time, and I’m not sure it matters to him. She’s just there to wait on him while he puts his estate in order and tries to finish his masterpiece. I’ll grant there’s something depressing about how one can only read one or two books a year and be in the top 50% of readers nationally, and I’ve met a lot of people who do seem to have an anti-intellectual antagonism towards difficult reading, but to write a deliberately obtuse novel complaining about the simplemindedness of the common people while being totally dependent on the labor of one of those people (the nurse) might strike most as hypocritical. My reaction was a few steps further. Amidst all the name-dropping the novel does to show off the intellectual power that produced it (and would, by extension, be required to understand it), Jung comes up, although I think we have to go a few decades back to one of Jung’s main influences, Nietzsche, to understand the actual logic of Gaddis’ underlying position. Perhaps this is due to the fact that I read Gaddis’ book at around the same time as Tutt’s How to Read Like a Parasite that I’m seeing the bridge, but there is a bridge that allows us to square the circle of Gaddis both complaining about the simplemindedness of the proletariat while also depending entirely on them for his existence. He is simply the latest in a long tradition who believe, as Nietzsche did, in a hierarchical social structure where the elect in its various guises ought to be given a free existence filled with otium (leisure time), while the masses, who would only waste such time if ever given it, ought to be kept busy making such a life possible. While Nietzsche may have been one of the most dynamic advocates of such a view, he was far from alone, as the historian Domenico Losurdo notes:

Authoritative historians of the time proceeded to make a comparitive study of the Prussian Junkers, the slave owners of the plantations in the southern United States and the feudal nobility in Czarist Russia. Despite big differences, all three of these social classes, whose splendour and the splendour of the culture of which they were protagonists was more or less based on forced labour, also had features in common at the ideological level: the celebration of otium was linked as a gesture of aristocratic distinction to contempt for productive labour. Identification with a refined culture based on slave or semi-slave labour went hand-in-hand with the proud distancing from the massification of democratic and industrial society, which was advancing impetuously and irresistibly and claiming to have the wind of history in its sails. Finally, mockery of the idea of progress encouraged a further gesture of distinction, namely the proud claim of ‘untimeliness’ as well as the ability to swim against the general tide of the world’s vulgarisation.5

Perhaps there is something more to be learned in Gaddis’ other work, which I’ve admittedly not read, but as of right now, I’m suspicious his work has much in the way of solidarity for me or any of my coworkers, classmates or friends, even if we’re the ones who may feed and change him when he and those like him need us most. Over Christmas and Summer break I tend to blast through reading piles and even get a bit of writing in here or there. School, and an eventual career in healthcare, are my limits. There’s much to be said about the current crisis of literacy, the general lack of readership and the decline in the humanities today, but so long as we’re going to have that conversation, I think we need to consider that reading (especially more difficult volumes) takes time and space, and consider how expensive those two commodities are today.

William Vollman, The Lucky Star (2020)

This was my first Vollman novel, and it almost seemed to have the opposite problem of Gaddis’ work. In and between every line is an aching pain the author has for his characters. They yearn, desire, lust, love, lose, are hurt and yet persist in the struggle to be themselves, a struggle hard enough for anyone, but especially difficult for the cast Vollman has pulled together. The bulk of the story centers around a gay bar in California where many of the members participate in drag performances while also looking for clients to go home with. Many are transgender, or queer, and struggle with combinations of poverty, safety and addiction, while those looking to hire struggle with loneliness. In the middle of this scene comes Neva, a woman sexually abused as a young girl and now cursed by a coven of witches to love and be loved by just about everyone she encounters. On the other end of the spectrum is Judy, a trans woman who takes turns giving blowjobs and asking her boyfriend, a retired police officer, for money, the result of which is usually some highly aggressive spanking and a $20 bill thrown her way, at which point she goes back to try and perform her routine of lip-singing to Judy Garland’s Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Sprinkled throughout, at the beginning of each section, are little epigraphs, half of them to biographies and memoirs of Judy Garland, the other half anthropological histories of sexual identity, the writings of the mystics, scripture and everything else. The result is a book concerned all at the same time with desire, lust, identity, celebrity and the sacrifice we demand of celebrities like famous actresses or Christlike martyrs in a bizarrely twisted, earnestly curious and deeply pained narrative. Also sprinkled throughout is a total lack of humor, unless you find Judy’s desperately confused attempts to figure out what it would mean to be and love herself funny, but I found myself more moved than humored by her. I think it would be understandable to say a trans woman who seems to have some cognitive limitations and spends most of the book switching between desperate, uncontrollable desire for Neva and getting brutalized by an ex-cop as he forces her to go down on him again and again and again is not the best trans representation, but in addition to finding her character moving, there was something honest about her to me. I’m not trans so perhaps it’s not my place to defend the character or the book, but among the many LGBT persons I’ve known (which is not many, but enough to have a decent sample size) I’ve seen fragments of Judy scattered throughout them. The difficult childhoods of rejection and self-exploration, the kinks, being somewhere on the neurodivergent spectrum, struggling to keep down a job, struggles to properly pass, the desperate search for self-understanding and acceptance, the patheticness of wearing the flaws that are endemic to all humans on their sleeves in a much more concrete and obvious way, and the eventual moments of joy when it all comes together, even if only for a moment. That these tensions all emerge in a drag-bar, a place where addictions of various sorts are commodified and sold, but also where moments of authentic self-expression can occur, also drives home the tensions that run through many of the patrons lives. Vollman’s book is painfully honest about the pains of being human, but between all the violence and abuse I felt a deep empathy throughout, like he was driven by a sincere desire to understand and connect with people. He isn’t cool or hip and he’s not writing about the queers to connect with today’s woke teens. My guess is kids these days would likely not like Vollman, but I’d say it’s their loss if they miss out on the sort of honest empathy I found throughout this book. I would not blame them, however, if they burned out halfway through. That’s about the point where I started to slip from intrigued and compelled to increasingly exhausted. The graphic depictions of sex and abuse, arousing and shocking at first, slowly turn into an exhausting and repetitive litanies, ritualistic like the mystical liturgies he cites, but exhausting nonetheless. Apparently he fought for some time with his editor to not cut it down and while I can respect fighting for your artistic vision, sometimes artists become their own worst enemy. There was good to be found in here, but much of it felt diluted in it’s 600+ pages. In spite of the fatigue I had upon finishing it, I’m not sure it would’ve had the same impact were it a more reasonable length. Maybe there’s a lesson in here that the novel seemed to be suggesting, the sometimes orgasmic bliss and religious ecstasy are intertwined with violence and brutality, and that the lesson of a great work can only be imparted by dragging the reader slogging through hundreds of pages that seem to go nowhere. I’m not sure. I’m glad I read it, but I was also relieved when I was finally done with it, and I don’t know too many people who I feel I could seriously recommend it to.

Greg Jackson, Prodigals (2017)

My interest was piqued in Jackson because he was the guest for my favorite episode of the Our Struggle podcast, an episode tragically marred by muted audio for much of it.6 The hosts seemed enamored with Jackson and his work, and Jackson himself seemed interesting so I finally found time this summer to read Prodigals and when I finished it I immediately went to the store to get a copy of The Dimensions of a Cave which I still haven’t even started at the time of this writing but the fact that I did it should convey my own enthusiasm for Prodigals, even if I’m admittedly not entirely sure where this comes from, and some stories definitely hit more than others. In the few remarks I’ve seen about it, people like to bring up the masturbation sequence in the first story and I’m admittedly sorta bummed about it, partly because I imagine a lot of people bring it up for a laugh. To be granted, it is funny and easy to laugh at, but it’s a really good scene too; well-written, detailed without being gratuitous or over-the-top, measured and makes good use of the moment to draw attention to the narrators thought process, the way he thinks about himself and the world around him. Without wanting to come across as boastful or egotistical, I also masturbate, [pause for applause] and I’ve often noticed my own thoughts wandering around before, during and after. The act brings fragments of joy, pleasure, relief, guilt, anxiety, fear, shame, catharsis, freedom and pieces of myself that I didn’t know were there, or maybe didn’t want to know or was maybe afraid to hold onto and pursue. We’ve already been beaten to writing the history of masturbation,7 but perhaps a phenomenological memoir via masturbatory fantasies is the next big thing in literature, just waiting for someone looking to cement their place in the literary canon. But if I just talk about the masturbation sequence, I’d be doing the rest of the story an injustice, and if I just talked about that one opening story I’d be doing the rest of the anthology an injustice. The book as a whole covers a lot more territory, although it all feels thematically consistent. Prodigals was the chosen title and it does fit, but it also implies a certain level of agency that I’m not sure all the characters would pick. Instead, many of them seem to have simply been living their lives, carried along by the inertia that everydayness tends to bring along with it until eventually they realize they’re lost and marooned. Some double down without realizing they’ve ever made a decision, while other try to retreat and get back. Some sit still and try to come to terms with where they’ve ended up. That the book was written and published in the twilight years of the Obama era also feels relevant; the cul-de-sacs of all these hollowed out persons seems to reflect the dead-end that a hollowed-out center-left liberalism was perhaps always destined to produce, leaving the way for something more savage as the usual sheen is finally ripped off of life. Perhaps this is me reading my own politics into it, but I do think it’s fair to place him, if not directly midstream, then at least in the shadow of the New Sincerity movement, one which I’m inclined to see as one of the primary expressions of the now-ending neoliberal era.8 What Jackson does in the era of increasing collapse and encroaching fascism will be interesting to see.

Marina and Sergey Dyachenko, The Assassin of Reality (2023)

I wrote last year that the Dyachenko’s have a gift for slowly pulling you into other worlds in such a way that the surreality doesn’t feel too jarring, allowing it to be all the more immersive and compelling. The Assassin of Reality was interesting in that it didn’t quite nail things with as much power or grace as the two books of theirs I read last year, and I have a few vague suspicions but nothing concrete in understanding why. Part of it is that Daughter from the Dark and even Vita Nostra to a degree felt somewhat self-contained, with a real sense of arc from beginning to end, whereas Assassin feels much more like a transitional book, picking up where VN left off and pointing to wherever this series is going. My understanding is VN and Assassin are the first two in a trilogy, with the third yet to be translated, and I have nothing against a book acting as a part of a larger whole. This is to say I wasn’t disappointed by the book, so much as it felt like a relatively flat appetizer, like an apple without much flavor. It felt smaller and less ambitious, which may prove perfectly serviceable once we can see the whole. Beyond that though, I think the book also fell a bit flat compared to the other entries because the authors at times seemed to be trying to explain the metaphysics of the world, when the sense of mystery VN and Daughter so carefully cultivated were really what pulled me along. Assassin is in the odd place of having to continue developing the plot which means trying to explain mechanics that are somewhat inexplicable. It’s a good lesson in how good worldbuilding needs to play out differently for different authors, and how less sometimes really is more. Some ought to leave the detailed stuff to Brandon Sanderson and Peter Hamilton and instead spend just a few pages sparking an itch in readers, getting subtle hooks just under their skin. The Dyachenko’s are clearly gifted, and I hope English-only readers like me get more chances to see it in the future.

Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory (1940)

With a title like this I had higher hopes. It was good, just not quite powerful and glorious. A priest in Mexico in the 1930’s is fleeing persecution, since the government is trying to do a religious oppression. He’s also a shadow of his former self, having succumbed to drink and fathered a child, and he’s often hesitant to perform the usual set of rites that are requested of him, either too afraid or too ashamed. Truth be told I think I’d like this one more on a reread cause there was some interesting stuff in here, especially at the end after he’s passed away. Throughout the book he’s still revered in places, and at the end he’s still faintly remembered via a souvenir left behind, the kind you can find in religious gift shops. I don’t have much to say about this one beyond that there’s an interesting intermingling of hope, despair and faith in a desperate situation. I wanted to like it, and maybe I’ll like it if I ever find time to give it another go.

David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (1996)

I first bought and started reading the copy I have in 2015 during my senior year of college. Lest I be accused of being a LitBro, I’ll say I burned out after a couple hundred pages and a couple months and returned the book back to the shelf, telling myself I’d get to it eventually, which turned out to be 2022 when I picked it back up and started from the beginning again. Older, wiser and better read in literature I did a lot better this time around, although I still found myself fatigued after a couple hundred pages, but more motivated to come back to it after a break. This became the routine then; read a couple hundred pages, burn out, read other things for a while and eventually return. I found that with every time I picked it up, it usually took me around 20 pages to find the books ‘rhythm’ again, I’d enjoy it for maybe 150 pages, then it would slowly turn into a slog for a few sections at which point I’d put it away, so there was joy to be had in reading it, just in smaller doses, but I’d be lying if I said I read it purely for the enjoyment. Ironically enough, the other thing that kept me going was a sort of spite, a desire to speak critically about the novel and about Wallace, but wanting to do so from a position of knowledge, or at least having gotten through the whole thing. I don’t want to be one of those who hate Wallace in a kneejerk kind of way cause I do think the work has serious strengths, which just happen to be diluted in a book of this size. It also has some flaws and is not as timeless as its defenders insist. Its suspicion of politics feels very much a product of the mid-90s zeitgeist, with the only politically engaged persons being a rather silly terrorist organization, while everyone else who finds salvation does so in a more personal, apolitical way. This stands out quite starkly against the dystopian future Wallace depicts of refugee crises, ecological destruction, the commodification and commercialization of everything including time itself and the stark class divides between those in the tennis academy and those in a rehab facility. Wallace depicts a world that is still struck through with deep political problems, and his depiction of the ways those politics become internalized as a sort of emotional solipsism are brilliant, but he can’t bring himself to suggest a political solution, only forms of personal salvation. This doesn’t make the book bad in my opinion, but it does make it frustrating to read with several decades of hindsight, and it seems to me to be more a product of a particular zeitgeist than a timeless classic, although for that reason it’s still worth reading as perhaps the best and clearest embodiment of a particular moment in history, with all its contradictions and limitations. In spite of all these qualifications, the book as whole is perhaps as close to a masterpiece as I read all year, with energetic and dynamic prose that explore big philosophical themes and is motivated by, among other things, a deep conviction that literature is important and capable of participating in history. It’s a bummer the book has gained such a weird reputation online because whatever my complaints about the book and its hype, the book deserves hype. Maybe not as much as some have said, but there are certainly worse books and writers to obsess over.

Sally Rooney, Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021)

Speaking of which, I decided to try Sally Rooney this year because I was hearing some different, contradictory opinions about her work (this was several months before Intermezzo was released and completely broke this site for a couple weeks, before completely disappearing as if it had never happened). On the one hand, some were saying that “She is a well-documented socialist and is committed to her Marxist critiques of capitalism and its parallel structures”, while others described her as insubstantial beach-reading. I was between novels when I heard that, so decided to try her with Beautiful World, Where Are You and came away incredibly confused, and it has admittedly taken some time to tease things out in my own head (which is why this section is going to take so long). The book mainly follows two girls, bumping through life and feeling a bit aimless, hitting a point where they should be functional adults by this point, but they’re not really feeling like it. Between the points where the plot actually moves along, they email each other back and forth about the history of capitalism, impending fascism and the bots they’ve started to see. If we put our literary-analysis caps on, we can assume Rooney may be trying to draw a connection between the decaying state of a world nearing apocalypse to the internal confusion the characters are feeling. Things slowly develop, everyone meets up, simmering feelings boil over in some conversations, but eventually everyone apologizes and the book ends with emails where both the girls write about how things have mostly been smooth-sailing in their newfound love-lives a few months later. If any Rooney defenders want to complain that I’m glossing over all the little details that make her work so rich and worth discussing, it’s because I want us to at least see the forest for what it is before getting distracted by the trees; some kids feeling the young-adult angst pretty intensely, but it largely dissipates as they grow up and settle down. Connected with the political angle (which is really only mentioned in emails, rather than made a substantial element of the plot), the takeaway seems to be that if you’re feeling radicalized by the state of the world, maybe settling down and starting a family would help assuage some of these feelings. I’ve seen some quite detailed breakdowns of some of Rooney’s scenes; the subtle dialogue choices, facial expressions, food being consumed and even fashion choices all being brought into play to explicate an underlying subversiveness to what Rooney is doing, but at a certain point I have to ask why a plot that is, in its overarching structure, fairly conservative and traditionalist to the point that it feels more reminiscent of a Hallmark movie than anything, being given so much benefit of the doubt? If people are seeking out something radical in their literature, why are we wasting so much time and space on Rooney’s work? And what does it say that this is what people think identifying and thinking as a socialist is? Beyond the girls occasionally lamenting the state of the world via email, nothing they do with their lives indicates anything terribly political. The only real political actor in the plot is Eileen’s love-interest Simon, who does work as an environmental activist, and his life committed to actually changing the world is often explicitly put in dialogue with his intense religiosity, but it’s also clearly a fairly prestigious position that pays a pretty penny. He’s not aristocratically rich, but he’s financially comfortable in a 9-5. Kate Morris he is not. All this adds up to a novel that confused me, not because of the book itself but because of Rooney’s bizarre reception as a sort of voice-of-a-generation writer, someone who has articulated the political despair and aspirations of the millennial generation. And perhaps she has, but not in the ways people mean when they say it. As Becca Rothfeld writes of her earlier work (in a way that indicates this is not a one-off problem of the politics but a consistent theme throughout her work)

a novel is under no obligation to double as a treatise. That it is a stretch to describe Conversations and Normal People as Marxist polemics is not a strike against them. Indeed, one of the books’ greatest strengths is that they capture, perhaps despite Rooney’s intentions, the impotence and hypocrisy that abound in the fashionably leftist communities she describes. When Connell tells Marianne that he was late to coffee because thee was a protest about “the household tax or something,” Marianne replies, “Well, best of luck to them. May the revolution be swift and brutal.” Then she and Connell get back to their convoluted relationship and their cappuccinos.9

And this is to come around to say that while I don’t hate Rooney’s work, because it is perfectly serviceable as beach-reading, it absolutely broke me to think that this is what a substantial portion of my generation considers to not only fine literature, but politically aspirational. I am a firm believer in the idea that politics can be found in art about the everyday; my favorite show is Mad Men, my favorite film is Y Tu Mama Tambien, and my favorite novel is, well, I don’t know, but a lot of my favorites all tie together the personal and political together in interesting and dynamic ways. Rooney does not, as Rothfeld writes elsewhere,

I don’t get the sense that the internal logic of these novels compels anyone to ask meaty thematic questions about self and genre. On the contrary, the internal logic of these highly enjoyable and slightly vacant novels compels their readers to sit down and indulge in some unusually well-crafted escapism. The meaty questions are an external imposition, a testament to the intelligence of those asking them and not to the intelligence of the novels themselves.)

Perhaps my negative feelings were somewhat exacerbated by the fact that I read Beautiful World shortly after finishing Infinite Jest, another novel with a very strong online reputation, albeit in another direction. Where Rooney’s work has been hailed by the progressive online as the embodiment of all its aspirations, Wallace has been mercilessly beaten into the ground, largely in response to a combination of his own personal problems (which are real and worth taking into consideration) and the way his work seems to have brought the most annoying type of guy (which is real, but way less real than the reputation built around him). Rooney and Wallace stand in a sort of bizarre contrast to each other, not just on the obvious stylistic level, but for the deeper thematic and political ones as well. Writes Anton Jager,

The difference between the generation-standard-bearing novelist David Foster Wallace (Gen X) and Sally Rooney (millennial) is a telling indication of the change. In Wallace’s world political conflict has been evacuated from a public sphere in thrall to commercialism and advertising, with only madcap terrorists actively dissenting. The result is a void that can only be filled with acts of individual re-enchantment or therapeutic group therapy. Rooney, by contrast, operated in a public sphere in which politics has clearly reclaimed its urgency, and collective notions o class have acquired a newfound plausibility. But the resultant posture is still fundamentally one of self-expression: a character may serenade her cleaner’s proletarian credentials, another may declare she is a Marxist, but it’s not clear what Marxist organization she’s a member of.10

As I’ve already said, I have my issues with Wallace and his apolitical politics, but in comparison to Rooney’s work his work feels much more politically prescient now than Rooney’s does, even three decades after it was published. Hell, Wallace even called back in the early 90’s that “unless neoliberalism is challenged, fascism will result,”11 and showed how a pleasure-obsessed narcissistic public might turn to a television personality who promises to keep our world clean and tidy while asking little of us to help build towards any sort of Common Good. Sure, it’s a thesis that had already been published a year earlier,12 and he was really just cribbing on Trotsky among others.13 Still, at least he got the thesis right, and developed the ways in which it might operate in our internal lives. It’s also just more dynamic, energetic and imaginative. It’s just better as literature, and I’m not sure that’s unrelated to the lame, impotent politics of Rooney’s work. She’s not so much a step back from Wallace’s limitations as a step away from the challenges they articulated, a step away from trying to use the novel to help expand our horizons so we might grasp the world (or at least a fragment of it), and instead turns so far inward in the hopes that nothing can touch it. Writes Sam Jennings,

Rooney is the great portraitist of the age — and that is precisely what depresses me. Because ours is an age so dreadfully and myopically concerned with its own psychology, often at the expense of everything else. What else but a self-obsessed culture would be so consumed with therapy as a substitute for life? The trouble with Intermezzo is just how little there ends up being in it besides this exhaustive play-by-play of human behaviour. In the narcissistic jail of contemporary life, Rooney is hardly a Prison Warden, yet neither is she a true accomplice in the escape. More like a priest on the eve of execution, there to dispense forgiveness but incapable of intervening in our ultimate doom.

To close this section that admittedly has gotten away from me, I’ll likely not be reading more Rooney in the future. Between my reading of Beautiful World and Rothfeld’s critiques, I feel safe in saying she has sucked up way more oxygen than her writing deserves and in a way that reflects a literary culture that is so bored and lost that it finds this sort of thing compelling, as well as a political culture that has taken the idea that ‘the personal is political’ so far that politics has entirely disappeared, eclipsed by personal navel gazing that has no place it could ever settle and be built upon. I have more thoughts along these lines, but they’ll have to wait for a standalone writeup some other day.

Norman Rush, Mating (1991)

Lest you all think I just agree with Becca Rothfeld on everything she says, let this stand as proof that I don’t. Mating is one of her favorite novels,14 and that’s fine, but it didn’t quite click for me. This wasn’t the same as Rooney not clicking with me; Rothfeld’s taste in literature didn’t drive me to despair over the realization that there is no hope, and there were at least glimmers of something more intriguing. Rush’s novel is clearly inspired by his time working in Africa with the Peace Corps, but it’s hardly biographical, instead using the location to ask some bigger questions of the time in which it was written. Published just two years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, most of Mating is spent in a sort of experimental, matriarchal village in the Kalahari desert. A young anthropology student makes her way there, although less because she’s interested in the village itself and more its esoteric founder, Patrick Denoon, one of the only men living there. The bulk of the book then bounces back and forth between lengthy explorations of the actual logistics of the village and the logistics of her relationship with Denoon, the Adam and Eve pairing exploring themselves and each other in this new post-Cold War African Eden. In all this, there was definitely an interesting parallel exploration going on between individual desires and political possibilities, questions that sometimes came up quite explicitly in various conversations. Denoon is torn at times between an idealistic hope that a better world is possible and a grim realism about how good a society human beings, with all their psychological and emotional baggage, can hope to create. The desert, and Africa more broadly, having been a victim of the last several centuries of political and economic plundering, are being given a chance to originate something new and better here, although the book itself seems somewhat ambivalent about where it thinks things are going. Apparently Rush expands on some of these characters in some later work, although this particular novel seemed to be more skeptical about what we can really hope for, and it ends on a note of critical cynicism, with our narrating anthropology student returning to the states and securing a variety of prestigious speaking slots and positions as she uses her experience to become an academic expert on the region. While this is a good critique of academia’s constant quest to commodify reality, turning it into archives that various experts go on speaking tours to extol the virtues or limitations of, I’m not sure we need to extend the cynicism to the actual village itself, but it feels fair to see Rush shares some of Denoon’s skepticism about what the future (of 1991) might hold. All this is very interesting thematically, but on a moment-to-moment basis, the book was not terribly interesting. I’ve seen a few remarks that the narrator’s dynamic and vibrant mind makes the world she observes intensely absorbing, but it just didn’t work for me. I wish it had, but ultimately this was one I found more thematically and conceptually interesting to think about than actually engaging to read. Maybe that’s a me-problem and I read it wrong, or maybe reading it right after Rooney spoiled any interest in anything romantic for me, or maybe I’m just not a vibrant enough mind to keep up with the narrator. In any case, Rush is clearly a smart guy who wants to tackle big ideas; he just didn’t do it for me here.

Sayaka Murata, Earthlings (2020)

I picked this up because

Honor Levy, My First Book (2024)

This was another one where contradictory statements led me to read it for myself. First,

Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (2022)

Apparently, for all the kids who aren’t irony-poisoned beyond any sliver of hope of redemption, things are actually pretty hopeful. They’re punks, but for hope. They call it hopepunk. And if that’s the sort of thing that sounds good to you, then Becky Chambers is the writer for you, at least with this very short and sweet little book about a tea-monk who meets a robot, and they go on a walk together. The world this all happens in is sort of the best case scenario for a post-apocalyptic society, where we overcame scarcity and now even while everyone has some work, everything seems pretty chill. This doesn’t stop Dex, the main character, from having a sort of existential crisis as they try to figure out the big questions about who they are and what they should be doing with their life, and the lack of any real tension from the actual world allows those questions to come forward with a little more clarity as they confront them. Then they meet the robot Mosscap and from there it’s basically My Dinner With Andre if Andre was a robot and Wallace Shawn was a nonbinary tea-monk (actually, that could work) asking questions about the nature of consciousness and the meaning of life. The lack of any major tension was admittedly kinda weird, but there was certainly a coziness to the text. It often felt like the written equivalent of lofi hiphop beats to study/relax to, with a calming dose of philosophical speculation on the side. It was nice.

Vladimir Sorokin, Ice Trilogy (2011)

This book felt like a much grander, more ambitious version of Earthlings. The similarity is you follow a cast of characters who are convinced they are not of this world, and see the world very much from the outside, seeing humans as meat-machines, society as a massive factory for meat-machines and everyday activities like eating, sleeping and fucking as being like any other activity to keep the factory operational. The expanded ambition comes from that fact that it’s a trilogy that covers the whole of the 20th century, a wider cast of characters, more space and a more diverse set of prose styles, often reflecting the particular character we’re following at the moments. The ‘normal’ characters get fairly standard prose, while the cult of outsiders get mystical prose with italics thrown in to emphasize certain words. It takes some getting used to, but the effect is to bring you into the minds of people who believe in the metaphysics of their revelation; that they are lost souls, children of the light who’ve become trapped in bodies made flesh, and that any means that might help them escape are vindicated, which leads to several hundred pages of kidnappings, torture, violence and slavery, but all delivered in a way where it might be real, and so vindicated. The conviction and certainty is muddled by occasionally skipping to characters who aren’t part of the mission, the prose reverting back to something more banal, which further accentuates how far away the mindset of those who are from everyday life. Whether the prophecy is true remains something of an open question, and the result is a massive book that remains unsettling until the very end, especially to anyone who might have the audacity to believe in things in this day and age. It’s a book about people in bubbles who see things in such a fundamentally different way than their neighbors that it demands basically a different language to describe the world, something anyone will be familiar when they stumble into a different side of social media than the one they usually occupy. If you think you’re not the one in a bubble, then this book is about you. That a book about epistemological bubbles came from Russia doesn’t feel coincidental, but the truth is that this problem is a problem of our time, not of any particular geographic region. How we get out of it is not made clear in Sorokin’s work, but he did articulate the problem in an incredibly entertaining way.

Nonfiction

Ben Agger, The Discourse of Domination: From the Frankfurt School to Postmodernism (1992).

This was a book that felt very much like a product of its time, for good and ill. Agger was a Marxist (of sorts), and here was interested in seeing what sorts of bridges could be drawn between Marxist theory and poststructuralism. This project feels very dated at the moment, and I’m seeing a general consensus that doing so mostly results in a sort of political dead-end, which means you have to read it somewhat charitably and accept that it maybe made a bit more sense at the time. It’s still an interesting read, especially as a sort of historical artifact, and it does have a lot of interesting essays, especially on Marcuse’s philosophy, and there are some important takeaways. I actually think his sympathy for the ‘postmodern’ turn in a lot of late-20th century leftist theory deserves more credit than it’s often given when put back into its own context. Mostly emerging from a lot of continental thinkers, especially in France, it gave us a suspicion of using dialectics to develop a totalizing worldview, questioned whether there was an underlying logic to history and moved away from militant class-action led by a vanguard party and more towards various forms of horizontal organizing. HOWEVER, this was in the context of a European left that was still struggling to find its way out of Stalin’s shadow, under which Marxism had been turned from a dynamic method of analysis into an iron law that permitted little real inquiry. The various leftist parties across Europe had their various struggles over how to deal with the ‘Stalin question’ and the result was various splits, where some decided to swallow their intellectual pride so as to stay within the party apparatus, while others went off on their own to try and chart new philosophical paths.15 Read with this context in mind, it becomes possible to go back and read various critiques of ‘Marxism’ as essentially attempts to salvage something emancipatory in a context where emancipation had been coopted into a new form of oppression, and it’s with that in mind that Agger is able to read some non-Marxist thinkers and salvage some helpful insights and point towards something better. I’m still not completely sold on everything he puts out, but I certainly agree with the charitable spirit in which he encourages us to read some of Communisms ‘fellow travelers’.

Perry Anderson, Considerations on Western Marxism (1979) and In the Tracks of Historical Materialism (1983).

These two books are part of a series of lectures Anderson gave over the course of several years, trying to offer a sort of genealogy of Marxist theory, especially in the wake of ‘68 but also taking numerous other currents into account, from the Frankfurt School to the French Existentialists, many of whom often identified or flirted with Marxism, but always with various qualifications and developments, pulling class theory into questions of culture, aesthetics, subjectivity and epistemology. In spite of its brevity, Considerations does an incredible amount of work trying to show how the philosophical development of Marxism has responded to changing material and political conditions, an excellent example of the materialist study of ideas at work. Crucially, he thinks many of the thinkers in the Western Marxist tradition started to develop their ideas in periods of defeat, be it the failed German revolution, the failures of the Soviet experiment, the turn towards fascism and World War or the failures of various postwar struggles. The left was in something of a dead-end, and some of the most famous texts of this tradition need to be read with that in mind. Anderson then argues that these failures led to a sort of inward turn towards more abstract, theoretical questions. Politics and economics were decentralized in favor of psychological or aesthetic studies. Rather than blankly and broadly polemicize against this, Anderson actually does think there are a lot of really interesting works that have come out of this tradition, but it has also eclipsed other important questions about revolutionary strategy and possibility. In spite of being almost 50 years old, the book didn’t feel terribly dated either; rewriting it today would essentially just require changing a few author and book titles and you could make a similar argument about today (which, funnily enough, Adrian Johnston essentially did in the latter sections of his Infinite Greed). Also still relevant today is the general hostility to Trotsky, or anything that smells remotely of classical revolutionary theory, which Anderson thinks we need to return to, ending Considerations with several suggestions, one of which is that we really need to study Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution. Unfortunately this suggestion has yet to be picked up with too much gusto, but Anderson’s critique of the dead-ends of late Marxism seem to be gaining some purchase among a disillusioned left intelligentsia, so maybe we just need to give it a little more time.

, How to Read Like a Parasite: Why the Left Got High on Nietzsche (2024).

Domenico Losurdo’s Nietzsche, the Aristocratic Rebel was translated into English five years ago now, and it seems to have inaugurated a revived leftist critique of Nietzsche, something we wouldn’t need if y’all had bothered to listen to Trotsky over a hundred years ago,16 but I guess late is better than never. The book quite thoroughly documents the reactionary character of Nietzsche’s philosophy, often assumed to be too esoteric to have much concrete political content, and was also a substantial influence on many left-leaning thinkers, particularly Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari. This adoption of Nietzsche on the left was deconstructed by Jan Rehmann with his Deconstructing Postmodern Nietzscheanism, brought into English a couple years after Losurdo’s volume. These two books, along with a host of others, have been forcing the question of Nietzsche’s reactionary side to the forefront of discussions about Nietzsche and leading to a reevaluation of much left philosophy of the last few decades, with Losurdo’s tome acting as a sort of center-of-gravity around which much of it happens. The only real problem I have with Losurdo’s text is its length, because in spite of being one of the most crucial texts to come out in the last decade its 1000 pages, no matter how readable, are likely to scare off many would-be readers. Fortunately Tutt’s How to Read Like a Parasite has stepped in as an incredibly helpful summary of some key ideas of Losurdo’s, as well as trying to draw out the practical ramifications for left politics today. He also does some work to see what can be salvaged from Nietzsche’s thought, but tries to stress that part of the danger in doing this is that Nietzsche’s thought has a tendency to develop a parasitic relationship to whoever bothers trying to wield it, even for emancipatory ends. In other words, trying to develop an emancipatory Nietzscheanism is playing with fire, but so long as you’re aware that it can burn you, you may be able to use it to illuminate a path forward. This isn’t to say Tutt is trying to develop a simplistic, uncritical Nietzschean-Marxism, just that he doesn’t want to throw out the baby with the bathwater. Like most people, I went through a bit of a Nietzsche phase when younger, one that has quietly impacted me in ways that all these books have allowed me to confront and dissect with a forceful clarity, and in a way that much of the rest of the left seems to be searching for. That this book was written by Tutt also drives home an aspect of his own work output, much of which is developing public-facing forms of philosophical inquiry, be it here or on YouTube, and with opportunities to participate in various study groups, and I’m glad he took the time to give us a much more digestible summary of an incredibly important debate. He’s a real one.

Dasha Kiper, Travelers to Unimaginable Lands: Stories of Dementia, the Caregiver, and the Human Brain (2023).

I’ve been working in memory care for a little over five years now, and while it has proven to be a very rewarding place to work, it is also exhausting, albeit in ways that are sometimes hard to explain. Yes, there are the obvious moments where someone calls you the n-word or you’re dealing with what we in the business refer to as ‘a blowout’ and I think most of you can probably imagine why this sort of stuff can be a bit of a drag. And to be clear, it is, but it’s also stuff you expect when you take on the job; incontinence, outbursts and confusion are all par for the course. What Kiper does a fascinating job highlighting, at least to me, are the more quiet ways in which dementia care takes a toll on caregivers by focusing the bulk of the book not on dementia or the patients, but on those who take care of them. In other words, it’s a book about my brain, and all the ways it has evolved that make dealing with dementia particularly difficult. Our neural wiring developed to help us cooperate and be social, and that means assuming a certain level of rationality in the people we encounter. Dementia essentially breaks this assumption, but also has a wily way of hiding, as patients often fill in the gaps of their memory with rather confident assertions. Just yesterday morning I brought a woman her pills, only for her to look at me, confused and annoyed, and say “I already took my pills this morning.” I had to shake my head and say “Nope, these are your morning pills,” to which she rolled her eyes and took them. If she fought for long enough I could maybe print something off, point to the clock and try to check her back into reality, but I’ve learned through experience that even that doesn’t always work. I have learned that evidence generally isn’t super persuasive with this crowd, although trust goes a long way, gained over a long period of time of just kinda hanging out in this weird alternate reality they inhabit. The difficulties Kiper teases out come from the fact that it basically means your own brain has to do double-duty, simultaneously keeping track of two parallel realities, one where someone is waiting for her husband to get back from a business trip and one where the husband is buried in some cemetery a few miles away. While not as extreme as the occasional outbursts of activity, it’s this extra workload your brain has to take on that slowly wears people down over time. Scientific intrigue aside, I found the book personally cathartic to read because it explained in a clear accessible manner why I’m feeling burned out from work. Yeah, maybe trying to balance it with nursing school isn’t helping, and obviously we’re all burned out cause of capitalism or something, but I would be getting burned out even were we in a Communist utopia and I decided to drop out. I have another year of school, so probably another year of checking into this parallel world once or so a week, and while there are times where I wouldn’t want to do anything else, I know there will also come a time where I need to do something else.

Andreas Malm, How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2021).

I read this back in the spring and at the time found the general argument fairly persuasive. I didn’t expect one of the first major instances of political violence to wade over into healthcare, but I’m overall glad to see people developing and redeploying the underlying theory. Malm has long been active both in climate activism and academia about the climate, although while this work contains plenty of footnotes, it has a much more accessible essayistic quality to it. Where Fossil Capital was an archival study, this little book tries to pull the reader on a journey towards the realization that the ruling class who have crunched the numbers and decided that while the planet might burn, it’s a worthwhile tradeoff. Admittedly I can’t really argue with them. Crunching some rough numbers, Tad Delay has calculated that keeping average global temperatures within 2 degrees would mean leaving behind $179 trillion worth of assets still in the ground in the form of oil, coal and natural gas. 1.5 degrees would mean leaving behind $227 trillion.17 That’s a lot of money, and beyond that there’s a lot of other economic and political inertia that would need to be rerouted to make this happen. Now, before you get all up in arms about how we can’t substitute individual vigilantes for a well-organized working class movement, know that Malm likely agrees. We can’t assassinate our way to eco-socialism or universal healthcare or any other much-needed social transformation. Nor is Malm saying that I, you or any reader of the book need to be the next Luigi Mangione. Instead he tries to demystify political violence, showing that the contemporary environmental movements aversion to it is something of an anachronism based on various historical misunderstandings. Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. come under some critical scrutiny, both for the times they used nonviolence (as a tactic within a broader political front) and the times they were a bit more open-minded. Malm is also aware that the mainstream environmental movement will not only have to avoid violence, but to condemn it. At the same time, he thinks it will benefit at the bargaining table from the stakes being raised. It’s warranted to wonder how environmentalists ‘raising the stakes’ might lead to more intense crackdowns even on peaceful parts of the movement, although I’m not sure what there is left to wonder about. I read the book in the Spring, as students occupied campuses in protest of a US-funded genocide, which often elicited violent crackdowns by the police. Perhaps blowing up a pipeline or assassinating a fossil-fuel CEO will just make things worse, but it’s hard to see how exactly. Legitimate forms of protest are becoming increasingly narrow, a whittling down of options that will only be intensified under the incoming Trump administration. Meanwhile the Democratic Party has spent the last several years telling even it’s moderate left dissenters to fuck off, which they promptly did, leading to a decreased electoral turnout, but the recent response to Luigi Mangione proves that it’s not because of a lack of politicized and radicalized consciousness so much as a sense of despair over the traditional modes of political expression. For the moderates among you who feel despair over our current situation, I’d recommend finding an organization that helps you connect to the struggle. For those who feel called and capable of something more drastic, I’ll not say anything, but only because I have a general rule of not encouraging people to do anything that I personally wouldn’t be up for doing. Best of luck.

Becca Rothfeld, All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess (2024).

I’ve already cited Rothfeld’s book, and I’m sure I’ve reposted some of her bits on this site, although I’m sure I first stumbled across an essay of hers in The Point without really connecting the essay to any particular person, cause the name in the byline tends to go in one ear and out the other. Or eye, maybe. In any case, I’d generally found her to be insightful, compelling and witty so I was curious to see what she could do with the space provided by an entire book. I’m still curious to see what she might do with a monograph, because this was a collection of essays, some previously published, around the theme of excess. Rothfeld’s basic contention is that we live in minimalistic times, but that we should learn to lean into excesses, the quirks and oddities of the human condition that make it human, allow it to stand out. As someone who lives in an apartment that is crowded out with books (stuffed shelves, piles on the floor, piles on various desks) and actually likes it as a counterbalance to my otherwise general aesthetic austerity (born mostly out of decorative laziness), I found the general thesis agreeable. It sort of reminded me of the essay about how nobody’s horny anymore, and Rothfeld thinks we could all stand to be a little hornier. Much of her discussion revolves around issues of sexuality, discussing various sorts of new puritanisms and the ways eroticism is being sanitized at the expense of, well, the erotic dimension. Other chapters focus on eating, or movies, or novels. She finds Sally Rooney to be a bit flat, whereas Norman Rush’s Mating is one of her favorite novels for its compelling descriptions of desire. As I’ve said above, I agreed with her on Rooney but didn’t see what she saw in Rush, and my experience with the rest of the book tended to waver back and forth between seeing her point and not quite knowing what she was getting at. Like lots of essay anthologies, there will be parts that really stand out in between essays that are also there, and which of those do which for you will depend on you, but the whole is more than the sum of its parts here, and my hope is that this book is really just an appetizer to a more thorough monograph, one that combines her interest in cultural dissection with the intellect she’s no doubt cultivating while working on her PhD at Harvard. Like I said with Honor Levy, books by young people tend to be fine in their own right but more exciting as announcements that something more interesting may be on the way.

Adrian Johnston, Infinite Greed: The Inhuman Selfishness of Capital (2024).

A few years ago, I read Johnston’s Žižek’s Ontology: A Transcendental Materialist Theory of Subjectivity. As the rather intimidating subtitle might suggest, it was filled with passages that read like this:

Instead of a linear developmental sequence running from an imagistic, intrapsychical Imaginary enclosed upon itself to a sociolingustic Symbolic transcending the solipsistic narcissism of the neonate, the very moment of Imaginary recognition is itself an overdetermined by-product of the prior intervention of the symbolic order, more specifically, the familiar big Other.18

In spite of the difficulty and density, the book goes in the esteemed category of rare titles where I can very clearly see (even if somewhat in retrospect) that there was a ‘before’ and ‘after’ I read it. In spite of the jargon and density of Johnston’s work, it has always managed to help clarify some rather urgent philosophical questions that cleared the ground for some radical political possibilities. Seeing those stakes in such difficult passages always took work, but it was always worth it, at least for me. With Infinite Greed, a lot of those political stakes that were often somewhat implicit and in the background are brought to the foreground, with questions of human nature and political possibility made much more explicit. You’ll see basic themes that Johnston has already covered in his rather voluminous career, so I’ll just respond to a couple things more specific to this text. First of all, Johnston often says he follows Žižek in trying to tie together three key fields (German Idealism, psychoanalysis and Marxism) into a revised theory of subjectivity, one that is simultaneously entirely composed of yet not entirely reducible to the substance it’s made of. Of that trio, Marxism has often been in the background, but has generally played a bit of a back seat. With this book it comes out much more clearly and precisely, and Johnston shows he is a rich reader of Marx’s work, particularly the economic studies, which sets him apart from a lot of other contemporary Marxist philosophers more drawn to trying to tease out a theory of culture or subjectivity from the earlier, more philosophically speculative works. Johnston’s focus on Capital felt refreshing, and his ability to tie it to the psychoanalytic work he’s spent so much time on drew out a number of oft-neglected layers to it. I’ll save my thoughts on Capital itself for below, but want to note that when I first read it several years ago, once I got through it all I felt the key to the whole thing was M-C-M’. This seemed to be to be the hinge around which everything revolved, and it was central to my own writing on the text,19 and also what I’d assumed was why so many had felt drawn to making connections between Marxism and psychoanalysis.20 As I dug further into Marxist scholarship, especially on the philosophical and psychoanalytic ends, I found more and more that this might’ve been a mistaken reading on my part, since it was a connection between psychoanalysis and economics that didn’t seem to come up much, so that fact that Johnston draws it out with much more force and clarity than I ever could was a relief, if only to find out that I wasn’t crazy, at least not for this. It also speaks to a larger point that Johnston makes in the final couple chapters on the ways in which much Marxist scholarship in recent decades has slowly detached itself from a material, economic base and turned into various forms of idealism, with a radical coat of paint to cover over the fact that they’ve largely left Marxism behind. Johnston essentially provides an updated version of Anderson’s Considerations on Western Marxism, and argues that Marxism needs to be returned to economics. This was not the argument I expected him to make with this book, but it was much appreciated, and extended his philosophical materialism from neural networks to economic ones. As with all of Johnston’s work, it’s not easy, but it is worth the effort.

Soren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates (1841/1992).

Of all the works of Kierkegaard’s that I’ve read, this one may have been the least Kierkegaardian. It still has a lot of his signature wit, but it’s more understated here. A lot of this is just a product of it being an academic dissertation, written for committee approval rather than spiritual provocation for that single individual, but it remained somewhat uncanny to read, since you could see the distinctive authorial voice underneath, peering through the cracks at times. You could also see it thematically; questions of subjectivity and psychology, explorations of literature and the history of philosophy, and the underlying quest to become a self are all there, but in a way that feels restrained and constrained. In spite of the restrained, dry academic style, it’s still one of my favorite works of Kierkegaard’s that I’ve read, no doubt enhanced by the aid of secondary sources,21 as well as reading at about the same time as I was reading Infinite Jest, which mentions Kierkegaard in its first pages, as Hal struggles to make himself understood by a committee. I’m not the first to draw attention to Wallace’s indebtedness to existentialism in general or Kierkegaard in particular, but it did help make The Concept of Irony feel more alive than it might’ve otherwise. The persistence of irony as a problem that may need to be overcome suggests it’s more than just a problem of the postmodern condition, but something more longstanding. Maybe it’s a product of a world overrun by markets, or maybe it’s an anthropological one that has always haunted us, and always will. We probably won’t see an answer for some time, but at least Kierkegaard gave us a voluminous account of how to understand and possibly overcome it, at least at the individual level. The Concept is also an interesting read as philosophical biography, in the way you can see themes coming up in a sort of analytic way, made explicit so they can be dissected, only to then give way to the much more literary approaches he would take in throughout much of the rest of his authorship. I’m not sure it’s the best place to start with Kierkegaard, but if you want to understand him you certainly need to read it eventually.

Karl Marx, Capital Volume I (1867/2024).

When I first read Capital several years ago, I was not a political radical of any sort. I was really a left-curious moderate, but also a confused college graduate trying to understand the world, and Marx appeared in a lot of footnotes to books I was reading so I decided, even though he was probably wrong about most everything. So reluctantly I picked up Benjamin Fowkes’ Penguin Classics edition of Capital (which maybe indicates a masochistic fetish on my part) and forced my way through it. By the end, I was thoroughly persuaded. Granted, there were other books that helped things along, but Capital stands tall as a sort of center of gravity for my own turn left. After finishing it, I spent several years trying to practice Marxism in the real world, time where I learned and grew a lot, trying to turn the theory into practical action. Returning to the text several years later, albeit in the form of a new translation by Paul Reitter, brought me back in a lot of ways to that experience several years ago and reminded me why I initially signed up, because being busy trying to make a revolution can sometimes make you forget why you ever wanted it in the first place. The mathematical equations, charts and graphs, dissections of political power and historical sweep are as powerful and persuasive as they ever were, but what really brought me back were the descriptions of the conditions of the working class, and the hypocrisies surrounding them. I first read the book while working 12-hour factory shifts, and I reread it after having spent the entire COVID pandemic working in healthcare, so it took very little imagination to see how the cost-cutting and labor-maximizing conditions under capitalism are still relevant today. Milder, perhaps, but the underlying logic is still there, and it results in similar enough situations. Marx does an admirable job of examining the conditions of factories and sweat-shops and bakeries and farms, looking up close at the actual working conditions capital’s logic produces, and he often does it simply by quoting official reports, medical surveys and bourgeoise newspapers. He’s not really muckraking; he’s just pointing out what everybody who wants to know already knows. Technology in the form of new machines allows for children to do work that used to be limited to grown men, but they’re just children so they’re paid less, so the employment of children becomes a necessary cost-cutting technique that factory owners insist they couldn’t manage without. Doctors are brought in to insist that it’s actually fine for kids to spend 6- or 8-hour days in hot factories that are poorly ventilated and filled with toxins cause they’re young and their bodies can handle it. Economists are brought in explain that if kids are taken out of the factories, labor costs will force everyone out of business. Everyone participates in a collective defense of child labor, slave labor, underpaid and overworked labor on every front, insists that even if not ideal, an alternative is impossible. What really broke me away from political moderation with this text was seeing what capitalism does not just to the workers, but to those who benefit from the system, or at least are kept enough out of harms way that they’re willing to make excuses for it. It corrupts the bodies of those who produce goods, but it also corrupts those who might defend it, who have to come up with excuse after excuse for the excessive barbarism and depravity it leaves in its wake. The editor of the new text, Paul North, starts his preface off by talking about Marx’s anger, his righteous fury that runs through the text. Generally there’s been a tendency, and I’ve not been immune from this, to try and downplay the emotional valence of the text, to try and uphold it as proof that capitalism is bad, and the proof is grounded in the mathematics. The charts, the graphs, the numbers. That’s important, but rereading the text over the summer reminded me that it wasn’t just that the text is argumentatively persuasive, but capable of emotional mobilization as well. Marx develops a totalizing vision of a world run awry by the logic of ceaseless profit, and then quotes some esteemed authority shrugging his shoulders and saying ‘Well yes, it might look bad, but have you looked at how we did last quarter?’ The conditions of the world are infuriating, and the hypocrisy that needs to arise to defend such conditions are even more so. Capital distorts us all, physically, mentally, emotionally and morally. As one viral post once put it, fuck this system and anyone who defends it.

All this reminiscence of my own journey aside, I want to say just a word on the translation itself. I read Fowkes as my sort of introduction to Marx, and the result was transformative, but also incredibly difficult. I found Reitter’s translation on the whole much more readable, and certain elements came through much more strongly, particularly his wit and humor. I also didn’t find myself fighting the sentences as much as with Fowkes, and it felt much more conversational throughout, allowing me to spend less time dissecting trees and more able to see the forest. There’s a possibility that this is just from my own personal experience coming to the earlier translation with no real context for what I was reading, only to then come at Reitter’s translation with several years of both concrete experience and consuming several shelves worth of secondary literature, I found the latter an easier reading experience. Were someone to say they were interested in reading Capital and was curious about which edition they should get, I’d first have to say I have not read the Aveling/Moore translation of 1887, so can’t comment beyond mentioning that Engels was apparently frustrated with it, and it likely has some rather dated language. Fowkes, meanwhile, is perfectly serviceable, and available in a very affordable edition. Reitter’s, however, stands out in my opinion as a substantially more readable translation, one in which the moment-to-moment experience will be substantially smoother, allowing for the larger vision to come across more cleanly. It’s not a step from total darkness to total illumination, but it does illuminate some things readers may not have previously noticed.

Carmen Maria Machado, In the Dream House: A Memoir (2020).

I read this for a book-club and it was serviceable as a memoir, but more interesting in the way it tried to draw attention to the limits of memoirs, and the broader ways in which certain genres and narratives sometimes get in the way of the truth. Machado’s memoir is of the several years she spent in a relationship with a woman that slowly turned hostile. Things start off well-enough, with lots of sweaty sex, fun outings, and road-trips that baffled the European members of the book-club.

Obviously things don’t stay in fairytale land, but what Machado seems interested in doing is trying to understand what it is that prevented her from understanding for so long. The book has numerous footnotes throughout, mostly to the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, sporadically connecting elements and moments of her own story to the larger canon of narratives, symbols and themes, trying to see if the archive of world literature might have answers, or some sort of meta-narrative on which she can impose her story. This is difficult though, because normally when people think of abusive relationships, they think of heterosexual ones, usually where a man is abusing a woman. That’s the narrative, and the archive is full of discussions of that. But a woman abusing another woman? The usual narrative of queer relationships is that they are an escape from oppressions, personal and political. A real shot at real freedom, self-expression and chosen communities. It hadn’t occurred to Machado that such relationships might contain many of the same problems, leaving her emotionally stranded for some time, unable to make coherent narrative sense of her situation. Eventually she does get out, but we are still left haunted by the time she spent with this other woman, wondering what other stories our archives might be missing, what territory our map might not cover, and what suffering might still be going on unnoticed.

Payen, Guillaume. Martin Heidegger’s Changing Destinies: Catholocism, Revolution, Nazism. Translated by Jane Marie Todd and Steven Rendall (Yale 2023).

Soderquist, K. Brian. The Isolated Self: Truth and Untruth in Soren Kierkegaard’s ‘On the Concept of Irony’ (Museum Tusculanum Press 2013); Perez-Alvarez, Eliseo. A Vexing Gadfly: The Late Kierkegaard on Economic Matters (Pickwick 2009); Burns, Michael O’Neill. Kierkegaard and the Matter of Philosophy: A Fractured Dialectic (Rowman and Littlefield 2015).

Kaner, Hannah. Godkiller (Harper Voyager 2023).

Tchaikovsky, Adrian. Children of Time (Orbit 2015).

Losurdo, Domenico. Nietzsche, The Aristocratic Rebel: Critical Biography and Balance Sheet. Translated by Gregor Benton (Brill 2019), page 672.

This is why

really should’ve hired me as the shows producer, because Drew was on a roll for a full 2 1/2 hours that are barely audible, a loss that will undoubtedly shape the literary canon for centuries to come. I could’ve stopped it.Laquer, Thomas. Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation (Zone Books 2004).

For more on this, I’d recommend Daniel Cult’s Post-Nut Sincerity and What Was the New Sincerity? He relies heavily on Adam Kelley’s New Sincerity: American Fiction in the Neoliberal Age (Stanford 2024).

Rothfeld, Becca. All Things are too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess (Metropolitan Books 2024), page 233.

Jager, Anton. “The Millennial Mind". In Granta 166 (Winter 2024), page 58-9.

Kelly, New Sincerity, 57.

Meszaros, Istvan. Beyond Capital: Towards a Theory of Transition (Monthly Review Press, 1995).

Roberto, Michael Joseph. The Coming of the American Behemoth: The Origins of Fascism in the United States, 1920-1940 (Monthly Review Press, 2018).

Rothfeld, All Things, chapter 12.

For more see Greene, Doug. Stalinism and the Dialectics of Saturn: Anticommunism, Marxism, and the Fate of the Soviet Union (Lexington Books, 2023).

Deutscher, Isaac. The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky (Verso 2015), pages 59-60.

Johnston, Adrian. Žižek’s Ontology: A Transcendental Materialist Theory of Subjectivity (Northwestern University Press 2008), page 54.

Dozeman, Stephen. Being Possible (Resource Publications 2021), page 77ff.

Dozeman, Being Possible, page 150ff.

Soderquist, The Isolated Self.

I really admire the style of these reviews!

Have you read Doris Lessing? I've read two of her novels, The Golden Notebook (1962) and The Good Terrorist (1985), both of which seriously engage with leftist/Marxist politics as a way of life. The Golden Notebook is kind of a proto-Rooney in that the main character is a writer, paralyzed about the political relevance of her novels, and unable to square her psychology with her political commitments (but she's in the Party, albeit somewhat ambivalently). Both books are now somewhat dated, and I have some artistic issues with The Golden Notebook in particular, but based on your reading I think you would find both interesting and rewarding.

the cover of Earthlings is such a trap… I read translated Japanese fiction a lot when I feel "burnt out" and I was recommending this to somebody and then had to be like… DON'T READ EARTHLINGS. DO NOT TRUST THE COVER.

Murata has a new book coming out this year so that may be the point at which I develop / publish my general theory of Murataism. But I don't think her thing is about social conformity exactly, though it's hard to pin it down in a "this is what it IS" way. Her short story collection is kind of helpful because you see her work through her whole deal in a compressed form (including a story that seems like sort of a dry run for Earthlings but which is about 200% less disturbing lol).

actually the combination of topics in your reading makes me sort of want to read Becca on Earthlings now! but it is a book I refuse to recommend to basically anybody lol. I think the people who have read it because of me are people who followed the exact same thought process as you.